Joi T Arcand - Canadian Art Review of Biennale d’Art Contemporain Autochtone

Exerpt from Review on Canadian Art Website

A look at the 4th BACA biennial reveals the difference between working in Indigenous ways, and working in Indigenous art—and Niki Little and Becca Taylor’s resolve to curate to and for their sisters

Following the initial publication of this review, BACA expressed concern about some of the claims made. Their concerns and our corrections have been added to the errata at the end of the text.

There are a few lines of thought that I want to lay out before I begin discussing the Biennale d’art contemporain autochtone—herein referred to by its shorthand BACA—the fourth edition of which ran at various venues in Montreal and Berlin this summer. First, the care, intelligence, and dedication that curators Niki Little and Becca Taylor put into organizing the biennale. Second, the uneasy environment of the current racial climate in Quebec for an organization such as BACA. The third line of thought is related to the shortcomings of BACA itself, at the head of which stands founder, president and director Rhéal Olivier Lanthier. In the preface of the BACA catalogue—a preface that appears before Little and Taylor’s curatorial text, and first in French—Lanthier identifies as a French Quebecer. My eyes widened when I saw Lanthier nod to his distant “ancestors,” one of whom he identifies as Onotawa’ka. The claiming of a colonized status in order to negate one’s role in colonial violence perpetrated on Indigenous communities on Turtle Island is a common settler move to innocence, as Eve Tuck might say.

Laying out these intentions, I hope to evade any confusion about my adamant support of the work of Little and Taylor, and the Indigenous art historical importance of their curatorial project titled “My Sister”—a package that I believe is the intellectual property of Little and Taylor and should be separated from the administration and infrastructure of BACA. Over the last year or so, I have been continually asked by my colleagues in art industries—curators, artists, critics and theorists within Canada and the United States—about the “Indigenous art trend” in Canada. I cringe every time. Indigenous art was, for centuries, the only art on Turtle Island. Indigenous peoples are due more than a moment to return Indigenous art to where it would have been if Indigenous territory, life and love had not been interrupted by colonialism. That said, what’s exciting is that Indigenous art in 2018 has seemed deeply rooted in the principles of rematriation—a term I borrow from the arts collective bearing the same name, whose art exhibits, happenings and uplifting memes featuring community have showcased positive representations of Indigenous women and recentred women’s knowledge within Indigenous communities.

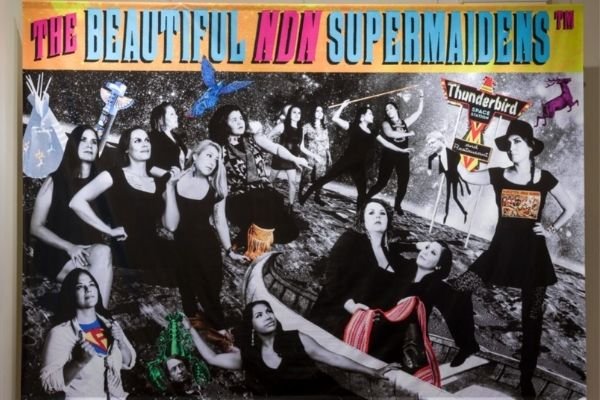

Joi T. Arcand, The Beautiful NDN Super Maidens , 2014. Photo: Guy L'Heureux

Activism was a central theme of Little and Taylor’s curation for BACA at the Musée des beaux-arts de Sherbrooke. Beaux-arts is a contentious term for me: I associate it with pretty art, and that community of folks who will curate retrospectives of the Impressionists until someone tears every last Renoir from their cold, dead hands. Beaux-arts doesn’t have a race consciousness. Well, except for orientalism, along with all its subject-object binaries that always seem to play to the sensibility and aesthetic tendencies of white folks. But what occurred at Beaux-arts during BACA was an intervention on said community. Joi T. Arcand’s The Beautiful NDN Super Maidens (2014) took up an entire wall alongside her NDN super-maiden trading cards. Known for her community-based, sexual-health art actions, Erin Konsmo, a youth activist who trained on the land under Christi Belcourt, exhibited a series of posters titled Landbody (2018). The posters towered as high as the French-colonial style columns inside the gallery. A series by Kali Spitzer of Indigenous women photographed in the style of anthropological, archival prints perhaps poked fun at the Québécois Beaux-arts crowd, who would love nothing more than to imagine Indigenous peoples into our graves.

Lindsay Nixon

Lindsay Nixon is a Cree-Métis-Saulteaux curator, an award-winning editor and writer, and a McGill art history Ph.D. student. They currently hold the position of editor-at-large for Canadian Art.